Examples

Interaction between magnetic field and excitons in CrSBr

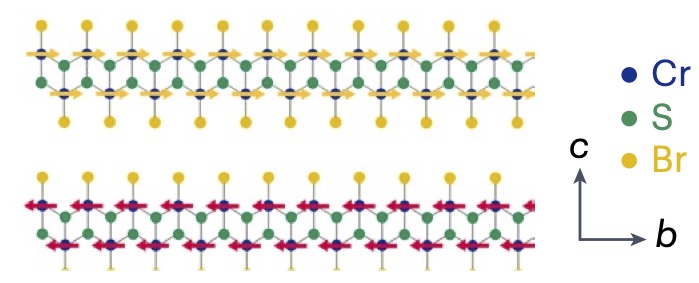

This post reports a continuation of our recent study of the optical response of excitons in few-layered CrSBr systems. CrSBr is composed of monolayers CrSBr, which can be stacked on top of each other. The layers are weakly bound by van der Waals forces. At low temperature, each layer orders ferromagnetically, but ordering between adjacent layers is antiferromagnetic (Fig. 1).

A new work looked at dependence of the optical response on photon fluence. The prior study investigated the contrast with the tightly bound exciton (called XA in the prior work, XL in the present one), and the more loosely bound, higher energy exciton, called XB in the prior study and XH here. A primary finding of the prior study was that the XA (aka XL) exciton divides into two distinct kinds: either confined to the surface or the bulk. (The two studies differ in that the former was done on few-layer CrSBr, while the latter were done for thick films. The XL exciton is about 0.1 eV larger in the bulk than in the few-layer case.)

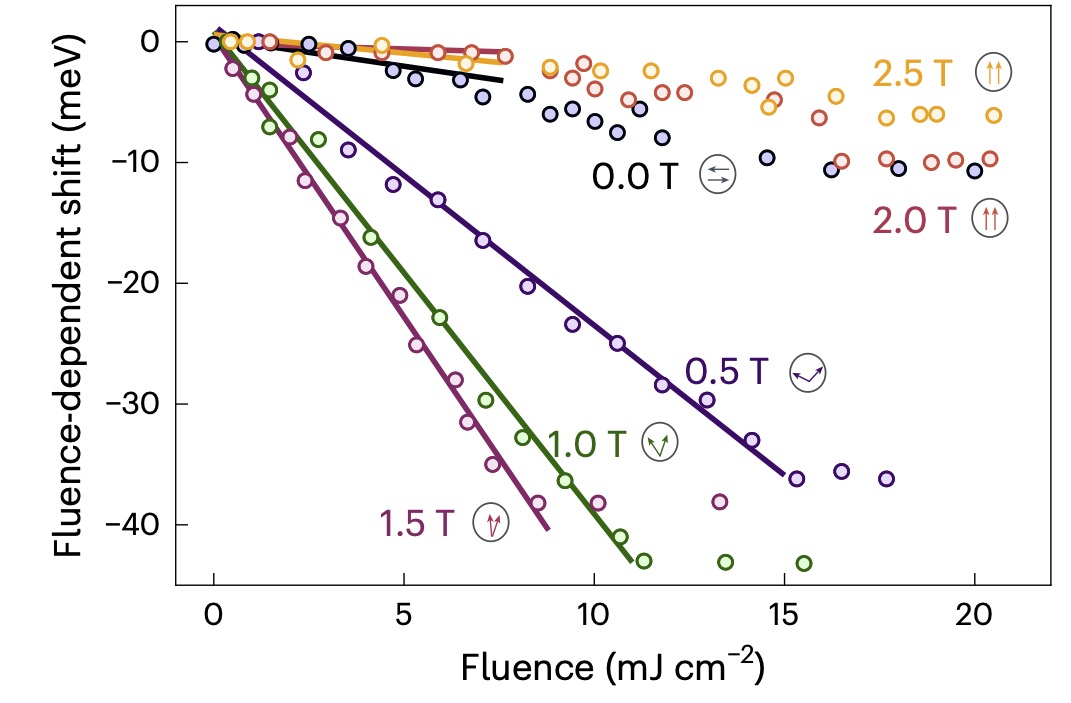

The study contrasts how XL and XH respond to high fluence and to magnetic fields. High fluence increases the exciton density, and provides a path to study exciton-exciton interactions. If the interaction coupling pairs of excitons is repulsive, the exciton energy will blueshift with increasing fluence; if it is attractive it will redshift instead. (It is not a priori obvious whether the interaction is attractive or repulsive since excitons are neutral objects.) This study also looked at how the application of a magnetic field modifies the fluence-dependence.

For both studies experimental results were interpreted by performing calculations in parallel, using the Quasiparticle Self-Consistent GW + BSE approximation. The high fidelity of this theory makes it possible to assert with some confidence new findings not directly accessible to the experiment (e.g. spatial structure of the excitons), or confirm that an experimental observation can be attributed to a particular mechanism, e.g. the state of magnetic order.

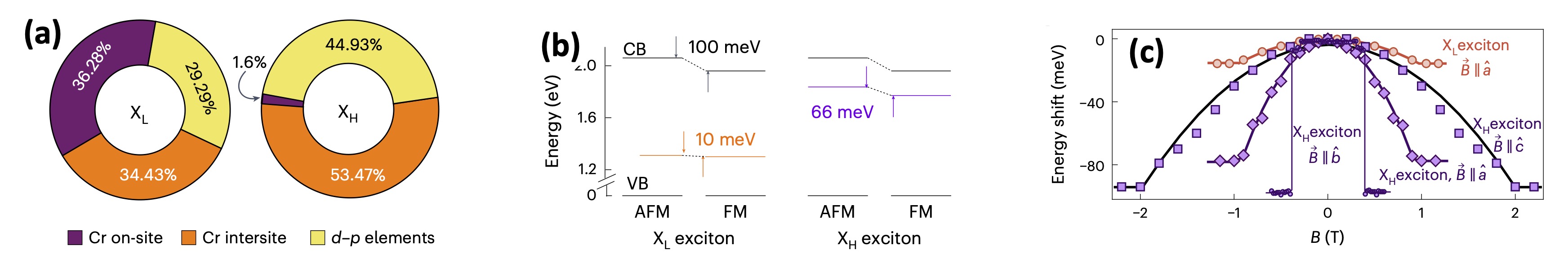

The present paper shows that XL and XH excitons respond very differently to changes in fluence and changes in magnetic fields. Both can be traced to the fact that XL is very localized (close to “Frenkel” limit), while the XH is much more extended (close to the “Wannier Mott” limit). While many details of the structure of this exciton can be found in the supplementary information, the difference can already be seen from the orbital-dependence shown in Fig. 2(a): the spatial structure of XL is much closer to the Frenkel limit than the XH.

Fig. 2(b) explains why the two excitons have different dependence on magnetic order. The transition from AFM to FM order changes the bandgap by 100 meV. (The reasons for this are explained in the present article and also in this reference.) The XL exciton is more atomic like, while XH is more band-like. As a result, the latter mostly tracks the conduction band edge while the former most the valence band edge. For that reason the XH changes by 66 meV with AFM→FM ordering (2/3 of the 100 meV gap reduction), while the XL exciton changes by only 10 meV.

Since the application of a magnetic causes spins to cant towards ferromagnetic alignment, we expect a gap reduction for both excitons, but more for XH than XL. This is what is seen experimentally (Fig. 2(c)). Note also that the change in XH binding depends on which way B is oriented. This is because the path the spins take as they cant towards total alignment with increasing B depends on the field direction. Once the field is large enough to “saturate” the magnetic order (make spins fully parallel), the gap reduction is between 80 and 90 meV, close to the 100 meV gap reduction predicted by the theory.

The primary aim of the experiments was to demonstrate exciton-exciton coupling, as measured by the shift in exciton binding energy with photon fluence, is tied to the magnetic field, thus suggesting a coupling tunable by a magnetic field. Indeed the change in XH binding energy with fluence, was observed to depend on B provided it was below the saturation field (Fig. 3).

Many of the findings of this work are supported by QSGW+BSE theory. While the theory is not advanced enough to provide definitive theoretical support for the role magnetic interactions play in exciton-exciton coupling, the theoretical component of this work was needed to explain the interaction of single excitons with B fields. This system has two co-existing excitons; one has a molecular (approaching the Frenkel limit) while the other is an extended exciton akin to those realized in crystalline solid-state semiconductors. Being able to calculate both in a unified framework with high fidelity, subject to varying magnetic order, made it possible to provide the essential insight into the experiments.

PAPERS · EXCITONS · 2D MAGNETS